Writing an Async Logger in Nim

2016-01-28 · HookRace · Nim · ProgrammingSurprisingly I’m working on HookRace again. I might share a few interesting code snippets and thoughts in this blog along the way. I’m still going with Nim as the programming language.

For an easy start let’s write a logging module that can be used everywhere in the game’s server as well as client. There are mostly three aspects that I care about:

- Can be configured to write to different files and/or stdout

- Writes to the disk asynchronously, preventing any blocking when the disk is overloaded

- Reasonable performance

Follow along if you want to witness how fun it is to write code in Nim!

Motivation

A few logger implementations for Nim already exist:

- logging: A simple logger in the standard library. Configurable, but no async writing

- omnilog: An advanced logger with lots of features, no async writing

- syslog: A bit too high level for my taste and no Windows support

We could adapt the logging or omnilog modules to our requirements, mainly by adding async writing. For now let’s write our own simple logging module from scratch instead. If it turns out to be usable after a few iterations one might merge it with an existing module. Also, this post would be rather boring if I just ended up using an existing logger.

Implementation

Let’s start with the simplest logger possible:

proc log*(text: string) =

echo text

log "Hello World!"We have a procedure log that is exported (*). It takes a value text of

type string and prints this text to the standard output. Super simple and

can be used like this from another file (or the same one):

import logger

log "Hello World!"This simply prints Hello World to the terminal for now when we execute it. We

want to keep using the logger in this exact format.

Next step: Add a fancy logging format:

import strutils, times

proc log*(text: string) =

echo "[$# $#]: $#" % [getDateStr(), getClockStr(), text]This uses the strutils and

times modules from Nim’s standard

library. The

%

operator formats the string "[$# $#]: $#" with a date, clock and our text

into [2016-01-28 20:04:43]: Hello World!

It would also be nice if we could see which module is actually invoking the logger. The instantiationInfo proc can be used to retrieve the filename and line of a template instatiation at compile time. So let’s make our logger a template, this also improves performance because we don’t even need a function call at runtime anymore:

template log*(text: string) =

const module = instantiationInfo().filename

echo "[$# $#][$#]: $#" % [getDateStr(), getClockStr(),

module, text]We end up with this output:

[2016-01-28 20:14:04][example.nim]: Hello World!

Let’s get rid of the .nim at the end:

const module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5][0 .. ^5] gives us the part of the string from position 0 (from the start) to

position 5 from the end. New output:

[2016-01-28 20:14:04][example]: Hello World!

Perfect! We’ll keep this exact output format.

Now let’s add the ability to log to multiple files simultaneously. We also just

handle stdout as a regular file:

type Logger = object

file: File

var loggers = newSeq[Logger]()

proc addLogger*(file: File) =

loggers.add Logger(file: file)

template log*(text: string) =

let

module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5]

str = "[$# $#][$#]: $#" % [getDateStr(), getClockStr(),

module, text]

for logger in loggers:

logger.file.writeLine str

logger.file.flushFileBy flushing the file we make sure that the output is actually written to the file right now, not just once the buffer is full. That’s important to us, for example if the program crashes and we’d lose the last few lines of the log otherwise.

Now we have to register a few loggers before we can log something, but that’s the only change:

import logger

addLogger stdout

addLogger open("example.log", fmWrite)

log "Hello World!"Now we write our log message to stdout as well as a file. If we used the

fmAppend file mode instead of fmWrite we could append to the log file,

right now we’re overwriting it every time we run our example program.

Here comes our main problem: What happens if we’re logging while the game server is running regularly, but the write to the disk takes a few milliseconds or even longer! The game server gets delayed and our performance is terrible!

Adding a Thread

So let’s add a separate thread to write the log messages. In Nim each thread

has its own heap, so we can’t directly pass a string to another thread. Instead

we will communicate with our new thread using a

channel, similarly to Go channels. We

start by defining a Message type to send over our channel:

type

MessageKind = enum

write, update, stop

Message = object

case kind: MessageKind

of write:

module, text: string

of update:

loggers: seq[Logger]

of stop:

nil

var channel: Channel[Message]We define three kinds of messages:

write: Write a new log messageupdate: Update the set of files to log tostop: Stop the logging thread

Our new proc for logging looks like this:

proc threadLog {.thread.} =

var loggers = newSeq[Logger]()

while true:

let msg = recv channel

case msg.kind

of write:

let str = "[$# $#][$#]: $#" % [getDateStr(), getClockStr(),

msg.module, msg.text]

for logger in loggers:

logger.file.writeLine str

logger.file.flushFile

of update:

loggers = msg.loggers

of stop:

breakThe thread keeps running until it receives a stop message. Calling recv on

a channel blocks until a message is received. Now that the main load is moved

to a new thread, what do we do in our log template and addLogger proc?

template log*(t: string) =

const module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5]

channel.send Message(kind: write, module: module, text: t)

proc addLogger*(file: File) =

loggers.add Logger(file: file)

channel.send Message(kind: update, loggers: loggers)Simple enough! We also need to initialize the channel and run the thread:

open channel

var thread: Thread[void]

thread.createThread threadLogNow we have to compile with nim --threads:on c example to get thread support,

or we simply add a nim.cfg that contains threads: on. Finally we run our code again and … nothing happens, no log message is printed.

The problem is that we finish the program too quickly. This kills the thread before it can receive our logging message. So let’s add a proc that manages the shutdown process more gracefully:

proc stopLog {.noconv.} =

channel.send Message(kind: stop)

joinThread thread

close channel

for logger in loggers:

if logger.file notin [stdout, stderr]:

close logger.file

addQuitProc stopLogThat’s it, our logger works! For more convenience we can add log levels and corresponding templates:

type Level* {.pure.} = enum

debug, info, warn, error, fatal

var logLevel* = Level.info

template debug*(t: string) =

if logLevel <= Level.debug:

const module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5]

channel.send Message(kind: write, module: module, text: t)

template info*(t: string) =

if logLevel <= Level.info:

const module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5]

channel.send Message(kind: write, module: module, text: t)

...What if we want to log not just strings? We can instead accept any kind and

number of arguments and stringify them automatically using $:

proc send(module: string, args: varargs[string]) =

var msg = Message(kind: write, module: module, text: "")

for arg in args:

msg.text.add arg

channel.send msg

template log*(args: varargs[string, `$`]) =

const module = instantiationInfo().filename[0 .. ^5]

send module, argsNow we can call our logger like this:

var x = 12

info "All ", x, " Bananas"[2016-01-28 21:57:34][example]: All 12 Bananas

For more advanced formatting one might want to use the excellent strfmt library:

import strfmt

var x = 12

var y = 3.4

info "{} + {:.2f} == {}".fmt(x, y, x.float + y)

info interp"I have $x Bananas!"[2016-01-28 22:24:01][example]: 12 + 3.40 == 15.4

[2016-01-28 22:24:01][example]: I have 12 Bananas!

Everything works great and we can be sure that hard disk latency will not bite us. But how is the performance?

Optimization

First let’s come up with a simple program that allows us to measure performance:

import logger

addLogger open("bench.log", fmWrite)

for i in 1 .. 1_000_000:

log "Hello World!"| Build Command | Runtime |

|---|---|

nim c bench (unoptimized) |

31.9 s |

nim -d:release c bench (optimized) |

12.1 s |

12 seconds to write a million log messages. I guess that’s good enough for my use case. We’d rather run out of free disk space than have too little performance like this.

Anyway, let’s see if there are any low hanging fruits. We could look at the

code and try to isolate some parts to figure out what takes long. Or we compile

the benchmark with debugger support using nim -d:release --debugger:native c

bench and invoke it with valgrind --tool=callgrind ./bench. Afterwards

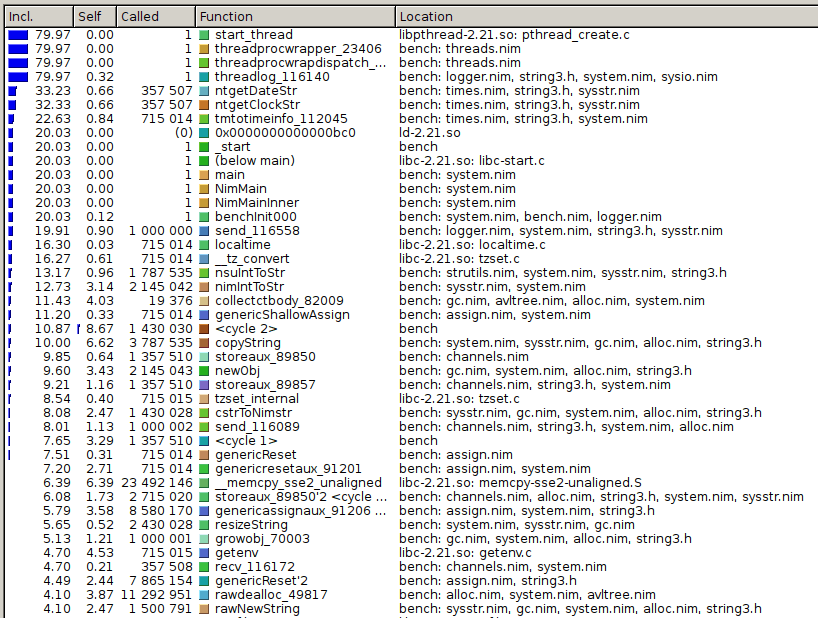

kcachegrind can help us analyze the function calls:

What stands out is that getDateStr and getClockStr take 33% and 32%

respectively of the total time! Since the time string only changes once every

second we can cache it:

proc threadLog {.thread.} =

var

loggers = newSeq[Logger]()

lastTime: Time

timeStr = ""

while true:

let msg = recv channel

case msg.kind

of write:

let newTime = getTime()

if newTime != lastTime:

timeStr = getLocalTime(newTime).format "yyyy-MM-dd HH:mm:ss"

lastTime = newTime

let str = "[$#][$#]: $#" % [timeStr, msg.module, msg.text]

for logger in loggers:

logger.file.writeLine str

logger.file.flushFile

...getTime() gets the time in seconds, so we only format a new timeStr when a

new second has arrived.

| Code Change | Runtime |

|---|---|

| Cache time string | 4.4 s |

Flushing the file after each write still consumes a lot of time. Unfortunately this can’t be seen using valgrind because valgrind’s instrumentation slows down the entire program so much that the flushing itself becomes insignificant.

The trick is to flush the file only when we’re actually done writing, that means when we have no more messages waiting in the channel:

if channel.peek == 0:

logger.file.flushFile| Code Change | Runtime |

|---|---|

| Flush only when necessary | 2.1 s |

A general tip when optimizing Nim code is to prevent string allocations and

copying. Instead of using writeLine we can add the newline directly and call

write:

let str = "[$#][$#]: $#\n" % [timeStr, msg.module, msg.text]

for logger in loggers:

logger.file.write strWe can use the same message and simply reset its text string instead of allocating a new one every time:

var msg = Message(kind: write, system: "", text: "")

proc send(moduleName: string, args: varargs[string, `$`]) =

msg.system = moduleName

msg.text.setLen(0)

for arg in args:

msg.text.add arg

channel.send msgThese two changes don’t have a huge effect, but it’s better than nothing:

| Code Change | Runtime |

|---|---|

| Prevent allocations | 1.8 s |

Another idea is to use a non-locking write since we only write from one

thread anyway. The POSIX C function fwrite_unlocked can easily be imported

and used in Nim:

proc fwriteUnlocked(buf: pointer, size, n: int, f: File): int {.

importc: "fwrite_unlocked", noDecl.}

proc writeUnlocked(f: File, s: string) =

if fwriteUnlocked(cstring(s), 1, s.len, f) != s.len:

raise newException(IOError, "cannot write string to file")

logger.file.writeUnlocked strUnfortunately this does not have any effect on performance.

So now we can log "Hello World" a million times in 1.8 seconds. For

comparison, simply printing "Hello World" a million times, without any

formatting or asynchronous writing, takes 2.4 seconds already when redirecting

stdout to a file:

for i in 1 .. 1_000_000:

echo "Hello World!"This is of course because of the flushing that happens internally in echo. If

we opt to use a raw write directly we can write the million strings in just

0.2 s, so there is still headroom for further improvements.

Final words

We implemented a simple logger, saw a few cool Nim features along the way and finally improved the performance by a factor of 6.

An even better optimization would be not to use channels for inter-thread communication. After all even the channels documentation notes that they are slow. Instead we could create a data structue in the heap shared between threads and use this. But I doubt that I will need more performance for logging, so this is good enough for now.

The resulting code of this post and future HookRace code can be found on GitHub.